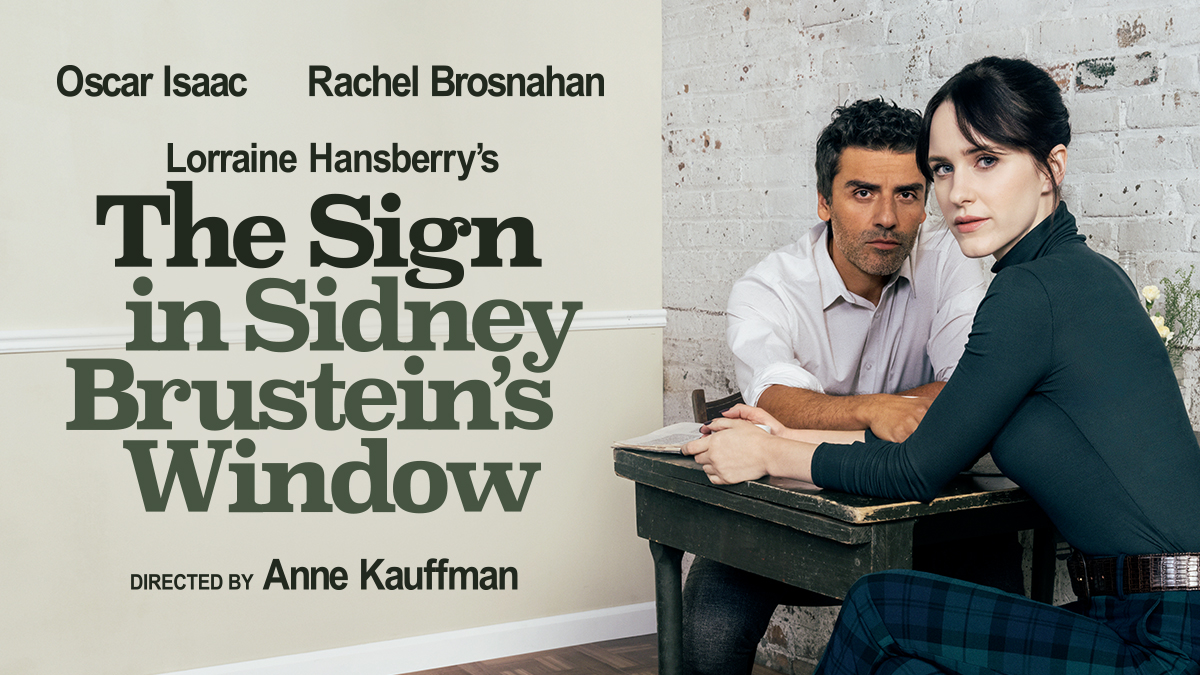

During the winter, a revival of Lorraine Hansberry’s “other play,” called “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window,” came to BAM. I didn’t see it there, but it was a hit largely because of two superstars in the main roles: Oscar Isaac and Rachel Brosnahan.

Hansberry was a superstar thanks to “A Raisin in the Sun.” Yet no one I know has ever seen “Sidney Brustein.” staged anywhere. It debuted on Broadway in 1964 and played a short, sad 101 performances. The anticipation was high because of “Raisin,” but it closed in 1965 right after Hansberry died from pancreatic cancer at the tragic age of 34. “Raisin” is her towering legacy. “Sidney” is her mistake. If she’d lived on, Hansberry would have known that and written several more plays that made more sense.

Now Isaac, Brosnahan, and newly minted Tony nominee Miriam Silverman have moved from BAM to the James Earl Jones Theater (formerly The Cort), where the novelty is gone and the problems with “Sidney” are evident. It’s a play without focus that feels like it was suggested by Neil Simon’s “Barefoot in the Park.” That’s all fine but Act 2 reveals the playwright had no idea of how to bring together those aspects with references to homosexuality, prostitution, communism, anti-semitism, and of course racism. It’s all too much.

All of the actors deserved a better play than this one. Anne Kauffman directs aimlessly, not even trying to make sense of the unwieldy. The actors enter and are charming. Oscar Isaac is powerful and fully present. He throws himself into Sidney’s misplaced idealism, Rachel Brosnahan is making her first move away from “Mrs. Maisel,” and she’s a star. Silverman, in her second ever Broadway production, is the find of the season. There’s even good news about Julian De Niro, son of Robert, who also makes his debut.

The show was panned in 1964, and looking back at the reviews, you can see why it was then and now. Isaac’s Sidney is a dreamer layabout much like the character the actor played in “Inside Llewyn Davis.” Sidney has a failure to launch, and he’s a little too old already. Brosnahan’s Iris, his wife, is younger, more realistic, madly in love with the idea of Sidney but wise to his failings. Silverman is Iris’s fake patrician sister, Mavis, who’s married unhappily to a rich guy and is condescending to this couple even though she has problems of her own.

Back in 1964, the New York Times dismissed the whole enterprise except for one scene with a secondary character, Alton Scales, the couple’s young Black friend, who tells a story about his father being condescended to by well meaning whites. Even now that scene resonates, and you think that Hansberry, if she could, would have rewritten the play to explore Alton’s world. It’s a shame she didn’t because in act 2 she runs out of material for Iris. This isn’t good news because when Brosnahan is off stage for quite a while, you can feel the air blowing through the James Earl Jones.

The two main actors have big careers, and you know we’ll see them on Broadway again. It’s worth seeing them, and Silverman, now, however just because of their commitment to the project. Their enthusiasm is contagious even when the play is letting them down. But listen, The sign in Sidney’s window should read “to let” after this. There are far better plays for these actors to do including “Barefoot in the Park.”