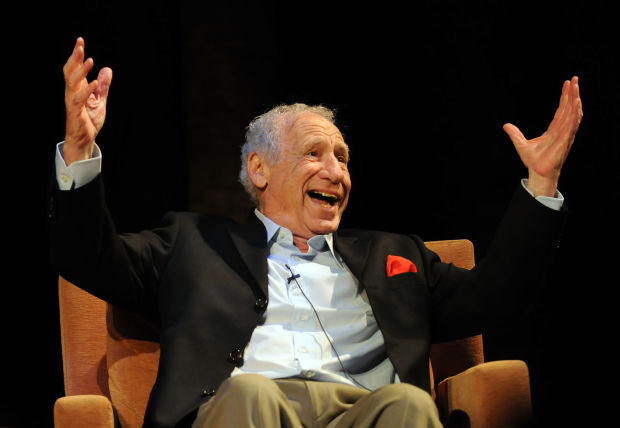

I know Mel Brooks is lonely for his real friends, like Carl Reiner, and his wife, Anne Bancroft. But we will have to do today.

Mel turns 95 today, and we love him. There is no one else like him.

What’s your favorite Mel Brooks movie? “Young Frankenstein”? “Blazing Saddles”? “The Producers”?

What about “Spaceballs”? I once played it for a bunch of kids after a Christmas dinner and their parents are still talking about it.

Favorite line? “It’s good to be king!”

And we’re not even getting into the musical of “The Producers,” which I could see over and over. The opening night on Broadway was one of the very best. “Springtime for Hitler,” the number with the little old ladies on walkers? Brilliant.

And let’s not forget Mel and Anne taking “The Producers” to Larry David’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm,” recreating the intermission bar scene, thinking the show is a flop. How wrong they were.

Here, again, is my 1993 interview with Mel. Long may he wave! From the sound stage of “Robin Hood: Men in Tights,” originally published in the NY Daily News.

Mel Brooks — just thinking about him makes me smile. What a genius, and such a lovely guy. In the years that followed he had so many more successes, particularly on Broadway with “The Producers” and “Young Frankenstein.” Happy Birthday, Mel! It’s good to be king!

“I’ve got the sound,” he proudly says. The sound,” he proudly says. The sound, as he describes his voice, is not just gravelly, it’s little-boy-like and accompanied by a Bugs Bunny grin. When he talks, his tongue hits the back of his pronounced eyeteeth, just avoiding a lisp. “It’s that first-generation American sound. We say boyd, woyk, and we have the scratchy sound. And we’re dentalized. There is a strange dentalization in my voice that I hear. I say, who is that person? It sounds like an immigrant.”

Brooks is part of a vanishing generation of Jewish humorists and novelists who came to prominence after having fought in World War II. He is 67, and although the tufts of gray and white hair might suggest otherwise, he looks about 10 years younger. “I don’t feel 67; I feel 27. I don’t feel a diminishment in any way physically,” he offers. “I sleep better than I did, and I think I could attribute that to getting older.” He also attributes a good night’s sleep to the upbeat response “Robin Hood: Men in Tights” drew at a recent sneak preview in Pasadena. Seems that even the prospect of a hit makes for sound sleep in Hollywood.

Brooks’ last hit was “Spaceballs,” a 1987 parody of “Star Wars.” “Do you know it’s my greatest income? These kids never stop renting this video. They tape it from television, wear it out, and have to rent it again,” he says.

Brooks’ last hit was “Spaceballs,” a 1987 parody of “Star Wars.” “Do you know it’s my greatest income? These kids never stop renting this video. They tape it from television, wear it out, and have to rent it again,” he says.

Recalling a recent 25th-anniversary celebration for “The Graduate,” which costarred his wife, Anne Bancroft, as the lusty and sinister Mrs. Robinson, Brooks says that “Dustin Hoffman unleashed his four kids on me and they all kept calling me me Yogurt. ‘Oh, look mommy, just plain Yogurt.’ They only wanted to know about ‘Spaceballs.’ They didn’t care about ‘The Graduate’ or anything I’ve done, like ‘The Producers.'”

His most recent film, however, “Life Stinks” (’91), bombed. And the suggestion that the movie was no good prompts Brooks to reply, “You’re being incredibly egotistical now. If you add for me [the interviewer], you’re forgiven.”

Indeed, a hit would be welcome relief. In Pasadena, he waited for the first laugh with the anxiety of a first-time director. It came, he says, “at the end of the opening credits, when the villagers whose village has been burned down in all the other Robin Hood films see my name and shout, ‘Leave us alone, Mel Brooks!'” It cracks him up just thinking of it.

For Brooks, there is no such thing as the politically correct – which is underscored by the range of people and subjects he has poked fun at in such comedies as “The Producers” (’68), “Blazing Saddles” (’74), and “High Anxiety” (’77). In “Men in Tights,” for example there’s a scene in which a blind man whittles at a wooden post unaware that a sword fight is swirling around him. It gets a lot of laughs, but does he care that public tolerance for this type scene may be changing?

“No,” he says without a hint of arrogance. “If I cared about being politically correct, ‘Blazing Saddles’ and all of that wouldn’t have hit the screen.”

He also never censors himself, and that, he says, sometimes invites criticism from Bancroft or from his four grown children. “I rely on my own taste. And if I know it’s witty, intelligent, and the heart’s in the right place, I know it’s correct. I’m always questioning the current socioeconomic values. I’m always pointing the finger.”

In the late ’50s, Brooks was one of a golden group of writers that worked on Sid Caesar’s “Your Show of Shows.” Along with his friend Carl Reiner, the group included Woody Allen and Neil Simon.

“It was a bunch of fiercely competitive and brilliant creative people thrown into a room together… everybody in the litter crying, screaming, to get the praise we lived for.”

But after working with Caesar, Brooks hit a rough patch. He was actually suicidal. “I was used to making $5,000 a week. I went from that to zero, unemployment insurance. I had three kids, alimony. It was a very bad period. But out of that came two great ideas: ‘Get Smart’ (’65) and ‘The Producers.'”

They would be the seminal Brooks works, his launching pads. “The Producers,” featuring the grandly insane musical number “Springtime for Hitler,” concerned two shady Broadway producers’ efforts to raise money for a guaranteed flop. It was based on a “bald man with an alpaca coat” for whom Brooks had briefly worked – and who charmed investments from dying old ladies.

The TV series “Get Smart,” a takeoff on “The Man From U.N.C.L.E.,” was co-written with Buck Henry. Brooks only wrote four of the show’s episodes, but he created the legendary CONTROL devices, such as Hymie the Robot, the Shoe Phone and the wholly inaudible Cone of Silence. “They can’t hear each other!” he chuckles. “And it has lasted to this day.

“I got a [royalty] check today for $50,000,” offers Brooks.

Brooks met Anne Bancroft in 1961, and they married in 1964. “I’d been dating Jewish girls with short waists. Here I had a long-waited beauty. She was singing on the ‘Perry Como Show’ when I met her. She was wearing a white dress and her voice was beautiful. She was singing ‘Married I Can Always Get.’ I thought, ‘Married I could be with her.’ I didn’t let her out of my sight from the day I met her.”

Bancroft, it seems, got his sense of humor immediately. “She understood; she laughed. She loved my mind,” Mel recalls, then “finally, over time, my face, my body. First my mind,” he quips, “which was much more beautiful.”

Brooks, born in 1926, grew up in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, as Melvin Kaminsky. His father died when he was 2, and his mother became the stabilizing force to four sons. “We were really poor,” he recalls. “My mother lived on welfare checks. Until my older brothers were old enough to work, we were living on handouts from her parents and my grandparents. But there was a great deal of joy and light in my house; I mean a lot.”

First cousin Howard Kaminsky, publisher at William Morrow Books and 14 years Brooks’ junior, says of the family: “He was brought up in the Depression and I think the family looked out for each other, but they had less, no question about it, than us. But they were very close, he and his mother and brothers.”

At 14, Brooks got a job working in the Catskills. “I played the district attorney in a play called ‘Uncle Harry.’ When I accidentally spilled a glass of water, I took my wig off, walked down to the footlights and said, ‘I’m 14, what do I know? It’s my first play.’

“I knew I was a comic,” he muses, “and the audience went nuts. The director chased me through the hotel, he was so angry. I knew then, straight drama was not for me.”

He spent a year in the Army in France and Germany in 1944 – and discovered Russian literature by reading “Crime and Punishment.” “When I stumbled across Dostoyevsky I said, ‘Jesus, this guy’s good! This guy really conveys such wonderful emotional thoughts.’ So I just stayed with Dostoyevsky until there was no more, every short story…”

Higher education for Brooks amounted to a year’s worth of credits from the Virginia Military Institute, but he claims, “I could teach Russian literature; I could go to NYU tomorrow and establish a course, get behind their thoughts.”

Brooks’ first marriage, to Florence Baum, ended after seven years, in 1960. They had three children, two sons and a daughter. He and Bancroft have a son. What kind of father was he? “I was nervous. I joked with them a lot. Sometimes they didn’t want to joke. They’d say ‘Daaaaad, get serious, I’m failing in geometry.’ I said, ‘So; I’ll tell you where Europe is.”

Divorced, he moved in with a friend, Speed Vogel, now a writer. Vogel recalls the Brooks would often wear his clothes. “He would write all over my walls, ‘Snore, snore, You kept me all up night!’ One day, when a friend called and I was sculpting, Mel told him, ‘No, you can’t speak to him now. He’s working on his horsie.'”

Vogel was part of a larger group of friends that included writers Mario Puzo and Joseph Heller who, beginning in the ’50s, met once a week and called themselves the Oblong Table – a smart-aleck set, so to speak, that schmoozed, debated and ate.

“I miss it a lot,” says Brooks. “I loved this basic primitive philosophy of asking animalistic questions like why are we alive?”

We’re standing alongside a gleaming white Range Rover that Brooks drives the 100 yards from the restaurant to the building where he’s working on the audio tracks for “Men in Tight.” “I go off the track in my car and in my comedy,” Brooks says.

Once inside the off-road vehicle, he turns on National Public Radio, and Fats Waller is singing “I’ll Never Smile Again.” Brooks hums along. You won’t hear any music after 1945 in here. They don’t write songs anymore!”

At our destination moments later, Brooks demonstrates why he needs such a vehicle in the first place. “Wanna see? I can do it,” he announces gleefully. So we wedge over a high curb rather than parallel-park conventionally – with a thump!

It seems like a metaphor for his manic career path. For a short, hot period in the ’70s, Brooks was on a roll. Between ’74 and ’77 came four hits. Barry Levinson, later to become the director of such films as “Rain Man” and “Diner,” worked as writer on “Silent Movie” (’76) and “High Anxiety” (’77). Says Levinson: “It was a great apprenticeship; I got a chance to watch [the whole process] unfold. You could argue about things; it was very alive and a great way to test material. I think I learned a lot. It opened up your mind to all the possibilities of film.”

But Brooks was dissatisfied with his life and work and took a self-imposed breather in 1981. “I thought, now I’m just become a crowd-pleaser. What have I got to say?” He had doubts about where to go next. “I couldn’t use my art just to make a living.”

He didn’t go the route of making sharply autobiographical films like Woody Allen. “I love ‘Zelig’ to distraction,” offers Brooks. “It’s his best movie; I was on the floor when he played one of the black guys in the band, just sitting around chatting. The fact that he could become anyone! And ‘Shadows and Fog,’ I enjoyed it. Maybe because I’m a film maker, there is always something edifying.”

Instead, he formed BrooksFilms and produced such movies as “Frances” (’82) and “84 Charing Cross Road” (’87), among others. He knows the public wants to see Mel Brooks movies, which often means low burlesque – not Brooks’ version of Bergman or Fellini. “I try to lace my movies with art, if you will. But not so that they’re weighed down by arcane and inaccessible references.”

Still, he succeeds best and exceeds the most as a parodist. Can he restrain himself from sending things up? “It’s hard, ” he admits. Later, when a young Englishwoman, a VH1 producer, tells him the time – half past three – in a proper accent, he does not miss a beat: “Okay,” he says, as the word pahst goes whizzing by him, “you can talk regular now.” The producer does not even hear him.

Afterward, he says, “I was ready to do Robin Hood years ago, but there was no reason to do it until I saw ‘Now they’re asking for it.’ Once I have something to chin on, I’m all set. With ‘You Frankenstein’ I had Mary Shelley’s story and all those movies. My job was not to tell the story; it was to make some switches on it.”

It is not lost on Brooks that a cottage industry has grown up around him, largely due to brothers David Jerry Zucker, who produced and directed such films as “Airplane,” “Naked Gun and “Got Shots.”

“Between me and you,” he says, “I don’t think they have the other side of it. I think they rush to the joke without an overview of choice and structure. They’re not from the school I grew up in. I grew up under the boardwalk in Brooklyn. Our mandate was to learn what this world was about, who was in it and why it happened. And we were well read.”

These days, Brooks reads works by friends Mario Puzo, Joseph Heller and Philip Roth, whom he calls “devastatingly funny. Roth and Heller are the two greatest book writers of this century. That’s our school,” he says of the last two. “We’re all veterans, all schooled in the fear of dying.”

The New Hollywood, with its cast of power players and brokers, does not hold much interest for Brooks. “I don’t need them; they’re just the current conveyors, packagers,” he says without a hint of bitterness.

Then, to a question about what he might see as an unchanging principle in moviemaking. Brooks, looking less manic, more tired, says: “The software is always the crazy Jew who gets it out; his name is Kafka. Do you know what I mean? Not [talent agencies] ICM or CAA. There’s always the marketplace. But the scream in the night never changes. That’s the eternal verity.

copyright c2020 Roger Friedman