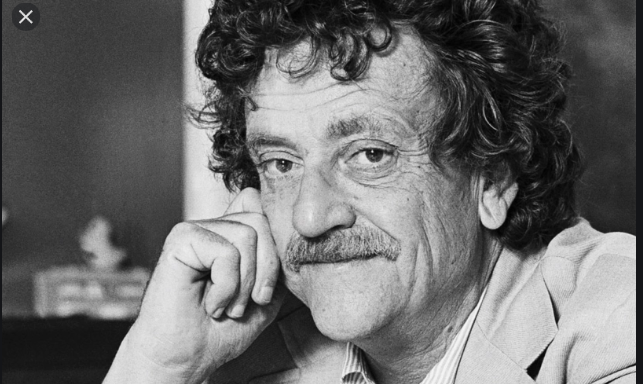

I interviewed Kurt Vonnegut for his 80th birthday in 2002. His wife, photographer Jill Krementz, helped put it together. I miss Kurt a lot (and so many others). Here’s the piece.

It was perhaps no mere coincidence in the grand scheme of the universe that the birthday of the great writer Kurt Vonnegut falls on Veterans’ Day.

Vonnegut, who becomes an octogenarian Monday, lived through the firebombing of Dresden, Germany, as an American prisoner of war in 1945. This seminal event became not only the basis of his classic novel Slaughterhouse-Five, but became the theme of his extensive anti-war writings.

Vonnegut has lived in New York and been highly visible for over 25 years. In some ways, I think that it may have hurt him.

The New York literati take him for granted. He still lacks some major awards, all of which he deserves. In the meantime, here is our reward for having Vonnegut in our midst: I spoke with him yesterday by phone from Los Angeles.

RF: I’ve been thinking about you since the talk of war has heated up recently.

KV: What happens on the ground is never spoken of, the number of people we kill with our unmanned kamikazes. The hawks would like to say we’re cowards, and can’t take casualties and all that, but it’s the inflicting of casualties that’s horrifying.

But this has become quite acceptable in modern warfare apparently — to kill a hell of a lot of innocent people in the process of getting one bad guy. And also I think this war is a very bad idea because it will never stop.

RF: President Bush appeals to the World War II generation….

KV: One of the great American tragedies is to have participated in a just war. It’s been possible for politicians and movie-makers to encourage us we’re always good guys. The Second World War absolutely had to be fought. I wouldn’t have missed it for the world. But we never talk about the people we kill. This is never spoken of.

RF: I just saw The Pianist, Roman Polanski‘s memoir of the Warsaw ghetto. When the main character finally emerges from hiding, Warsaw is destroyed. The first thing I thought of was you in Dresden.

KV: Warsaw’s condition was particularly interesting. German engineers undermined all the prominent buildings. That’s why there was nothing left. They wanted a Slavic capital.

RF: Are you amazed that you lived through the devastation of Dresden?

KV: No. I think I was the luckiest guy in the world. I wouldn’t have missed it. I got to see so much.

RF: Are you surprised that Slaughterhouse-Five is still so popular? Do you still get mail?

KV: My fan mail is the size of Eddie Fisher‘s, I think.

RF: Do people write to you as sort of armchair Kilgore Trouts, experts on things?

KV: These people are called schizophrenics. [Laughing.] They know all about the flying saucers.

RF: Seriously, your work has lasted. My friend still teaches a course on you in her high school.

KV: It’s just like going to Las Vegas. Maybe you win and maybe you don’t. I wrote what I had to write for whatever reasons. Apparently it was my destiny to write as I have, and yes we found readers.

Do I have a survivor’s syndrome after the Dresden firestorm? I have a survivor’s syndrome about all the wonderful writers I knew who ended in neglect and abject poverty.

RF: You’re thinking of people like your old friend Richard Yates [the great novelist and short story writer, author of Revolutionary Road]?

KV: Of course … In one book I told about a guy who rebuilt my house up in Cape Cod. He did the whole damn thing, put the footings in and the foundation, and when I asked him how he did it, he said he didn’t know.

I look at the list of books I’ve written and it’s not much of an output. I’m completely in print and how the hell I did it, I don’t know.

RF: Is there one book you’re more partial to than the others?

KV: The flagship of my little fleet is Cat’s Cradle.

RF: Personally, I find myself thinking of Norman Mushari from God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater all the time. I see a lot of Musharis in my line of work.

KV: They’re called lawyers, I think.

RF: They’re sneaky lawyers.

KV: Thinking of Mushari, I’ll tell you about a terrific book. It’s called The Mask of Sanity. It’s a medical textbook that’s out of print written by Dr. Hervey Cleckley, now dead.

And this book should be brought into print. It’s about psychopathic personalities.

This is certainly a symptom of what these executives at Enron and other places are like — psychopathic personalities. They have no conscience. They know the consequences of their actions and do not care.

RF: Are you actually writing another book?

KV: I am trying. I didn’t expect to live this long. As an actuarial matter, novelists and short-story writers do their best work when they’re young.

RF: But I loved Timequake. I was very disappointed when you said that was it.

KV: That’s friendly, thank you.

RF: Well, I mean it, and I think your fans will be thrilled to hear you’re still working. Happy birthday, Kurt.

KV: You know what they say. [Taking a beat]. If you think I’m a mess, you should see what Mozart looks like by now.